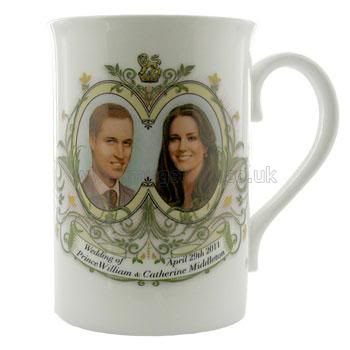

This morning I watched clips from the Royal Wedding at Westminster Abbey. Pardon me while I make a pit stop at CNN.com to get the names of the bride and groom. Right. Prince William and Kate Middleton. Some thoughts:

This morning I watched clips from the Royal Wedding at Westminster Abbey. Pardon me while I make a pit stop at CNN.com to get the names of the bride and groom. Right. Prince William and Kate Middleton. Some thoughts:1. I wouldn’t like to curtsey to my grandmother-in-law on the way back down the aisle.

2. What’s with the forehead hats? How do they stay on?

3. Eye shadow in the brown range might have been a better idea for Kate than that Gothic dark gray.

4. Prince William is (obviously) going bald. Is that the result of stress or, as bald men would have us believe, a superfluity of testosterone?

Everyone looked nice, even those with forehead hats, and I was happy to see that Elton John was in attendance. I’m not hugely talented or fabulously rich or a gay man, but he always makes me feel as if I have a representative at these events—someone who might get a little drunk at the after party and speak some small truth.

When I was teaching at a community college in east San Jose, California, my classes were mostly made of first and second-generation immigrants—from Vietnam and Mexico, Central America, Africa, the Middle East. A fair number were not yet citizens. Some may have been illegal. I had no way of knowing and didn’t much care.

Discussions in my Critical Thinking classes often wandered, or maybe came down to, the topic of birth. Many students believed, or found it expedient to say, that America was the greatest country in the world. Some had risked their lives to get here. If their parents both worked two jobs to keep food on the table, if they themselves worked nights and weekends while going to school, that was temporary, a small price to pay. Eventually they would be every bit as American as, say, George Bush.

Occasionally a student—one in particular, I remember, was from Palestine--suggested that he would never be considered truly American by people who were born here. And for this reason his opportunities—it took a lot of courage to say this—might be more limited. Some students, usually also immigrants, were enraged by comments like this. People who never spoke in class raised and waved their hands until I called on them. My native students, especially the white ones, typically kept quiet. I don’t know if they feared the speaker was right, or looking into their own hearts, knew he was.

In the interests of transparency, in Critical Thinking classes especially, I made it a policy during the first class session to out the most general of my views on life, the universe, and everything. After that, however, I tried hard to keep them to myself. Discussions about birth and human value almost always drove me to break my rule. “Who decides where and in what circumstances we’re born?” I said at least once a semester. “Who deposited me in the body of a white baby girl with a particular set of parents in mid-twentieth-century Sacramento, California, USA?”

Usually about half the class replied in unison: “God.”

“Okay,” I said, “maybe so, but does that have anything to do with what I deserve from life, how comfortable or uncomfortable I ought to be, how happy I am? Did God choose my birth based on my virtues?”

Some confusion here, but most students ultimately agreed that we get what we work for, that life, starting from birth, not from some nebulous place before birth, is a meritocracy—just like the United States of America. I don’t believe that for a second, but I didn’t go down that road.

“So we have no business pretending that we’re inherently better than others or less than others based on the details of our birth?”

Hesitant agreement.

“What if you don’t believe in God, or at least not in a god who’s the Big Master Planner? Doesn’t that mean that where you’re born, who your parents are, all that stuff, is just random, a crap shoot?”

Occasionally a student brought up karma and reincarnation at this point, and I invited her to explain those ideas to us.

I never let this discussion go on too long. Luck—and that’s what this is all about—is a deal-breaker for some, the first domino that knocks all the others down. I had good reasons in a class like Critical Thinking to be luck’s temporary spokesperson, but I didn’t want to jar that first domino. “All I’m saying is that the circumstances of our births may be accidental, and even if they aren’t, unless we had previous lives--" I nodded to any Hindu or New Age proponents—“our births say nothing about our fundamental value. We don't earn them.”

If this discussion changed the direction or tenor of my classes, I couldn’t pretend then, can’t pretend now, to say exactly how. But I remember this morning, as Kate Middleton joins the royal family of Great Britain, scoring all those wardrobe choices and fine wines, summers in Scotland, winters skiing in the Alps, stifling dinner conversations and boring social obligations, that her birth was an accident, too. Does she deserve all that stuff? No. Do I? No. Does a child born today in the Congo or Bangladesh or Rio’s favelas? Probably not, but those new babies matter as much as William and Kate do.

Here’s where I go off the rails.

Those children matter more.